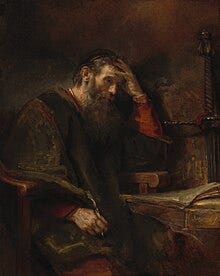

The Mystery of the Apostle Paul — and What Was He Reading?

Some recent articles on Medium have revived my interest in an issue I’ve addressed before. What follows next here is the background to the article below.

At the beginning of this article the Christian writer Kyle Davison Bair quoted the apostle Paul from 1 Corinthians 15: “…that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures…” This triggered a memory from several years ago; I was reading a commentary which said that this passage has left scholars “scratching their heads” wondering which scriptures Paul was referring to.

The problem is that there are no obvious relevant passages in the Old Testament. I therefore replied to Bair, asking him if he knew. In his response he agreed that “there are no Old Testament passages that predict Jesus being buried for three days”, but claimed that “this is one of the ways we know that the gospel of Matthew was published early, and Paul was familiar with it”. His reason for this was that there (12.40) Jesus said: “For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” He concluded that “this provides us with early evidence that Paul is familiar with Matthew, and considered it scripture, on the level with the Old Testament books”.

This is obviously controversial since, according to conventional scholarship, Paul was the earliest Christian writer and the gospels were written later. I put this to Bair, and in his response he said that he dates Matthew before Paul wrote 1 Corinthians. (He has defended his view of the early date for Matthew here.) This is still obviously a controversial viewpoint, and in an exchange with ShirleyM we agreed that Bair is a Christian apologist. Bair has responded to that accusation here.

I therefore turned to other Medium sources to see if they had any ideas about what scriptures Paul was referring to, firstly to Evan LeBlanc. As his articles demonstrate, he has an extensive knowledge of the Bible and Christianity in general, and thinks deeply about them, often outside the box of standard Christianity. I felt sure that his thoughts would be worthwhile. (He says that he is a Christian with liberal ideas. He has a Master of Divinity degree in Hebrew Bible. He is strong in Hebrew, competent in Greek, and has some knowledge of Aramaic, Latin, Akkadian and Middle Egyptian, therefore takes the subject very seriously. He has also served as an assistant minister.)

His full response can be found here. For my purposes the main points to be extracted are that:

- “it is impossible to assume what specific passages are in view here, but I think the idea is that Paul is passing on this tradition that the Hebrew Bible is the foundation for the Jesus movement”

- “the word scriptures here could refer to other prophetic writings or books outside the Torah that made it into the Hebrew Bible”.

He also rejects Bair’s assertion that Paul might have been referring to the Jonah verse in Matthew, also reiterating that “the gospels are likely a lot later than this passage”.

I also consulted someone writing under the pseudonym of Religion and Politics at The Dinner Table. He was brought up in a conventional Christian tradition, and has an extensive knowledge of the Bible. He now writes articles exposing the flaws, as he perceives them, in Christianity. For him this serves as a form of therapy, to help him recover from his upbringing which he now rejects.

His full response can be found here. He agrees that there are no obviously relevant Old Testament verses, but mentions some which have been deemed to be so — “as with all the other instances, Christians see in it what they want to see” — although other interpretations are more likely. He thinks that Paul “seems to be merging various obscure scripture references and trying to form them into the narrative he wanted, as we see done with so many aspects of Christianity”.

===============================================================

EDIT

When I wrote the above, I had failed to enquire of Bair his qualifications. He has subsequently informed me that he also has a Master of Divinity, and has learned Hebrew and Greek. He is therefore well qualified. I have apologised to him for this omission.

===============================================================

That concludes the background to the main thrust of this article which now follows. I think we have established that Paul is definitely not referring to Old Testament scriptures in the quotes above. LeBlanc and Religion and Politics are probably not aware of at least some of the material that follows. I’m going to address the possibility that there were some actual scriptures that Paul was referring to, scriptures that the world is no longer familiar with, therefore that:

- the idea that Paul is passing on the tradition that the Hebrew Bible is the foundation for the Jesus movement is an oversimplification, that there were other sources

- Paul is therefore doing more than “merging various obscure scripture references and trying to form them into the narrative he wanted”.

Some of what follows may be considered by some readers hypothetical and speculative. I offer it as a point of view. I would obviously be grateful for any responses which challenge it, provided that they are based on genuine knowledge.

It is vitally important to understand Paul because much of later Christian theology is based upon his writings. He is controversial because for many he is the villain in the story. For example Religion and Politics at The Dinner Table has written an article recently claiming that the teachings of Paul are in contradiction to those of Jesus. That is a fairly mild grievance compared with those of the following.

Another Medium writer Keith Michael, author of FALSE WITNESS: How the Christian Church Built a Foundation of Lies, fulminates against Paul. In Islam he is considered to be a false prophet who deviated from the true teachings of Jesus (see for example The Mysteries of Jesus by Ruqaiyyah Waris Maqsood). The same argument is made by conventional Judaism (see for example The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity by Hyam Maccoby). The main argument (of the latter three) is that Paul introduced pagan elements into his new religion which deviated from the original true teachings. With that in mind, let us try to delve more deeply into Paul and his life. What follows is what we know according to the New Testament texts.

Paul says that prior to his conversion he was extremely hostile to the Jesus movement, persecuting the “church of God”, and “trying to destroy it” (Galatians 1.13) According to Acts (22.4) he persecuted them “up to the point of death”. He says that he was brought up in Judaism, even beyond his contemporaries because he was “far more zealous for the traditions of my ancestors” (Galatians 1.14). He was “as to the law a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless” (Philippians 3.6). He was therefore something of a fanatic.

The obvious conclusion, despite the claim of some scholars that Jesus was essentially Jewish, is that the early Jesus movement was in profound disagreement with the Judaism of the Pharisees; it must have been an entirely different tradition, otherwise why would Paul be so vehemently persecuting it? Before going into more detail about Paul, it is therefore important to try to understand what tradition he was being converted into. What exactly was the Jesus movement?

There is ample evidence for this conflict in the gospels. Firstly, there is Jesus’s vitriolic attack on the Pharisees in Matthew chapter 23. Especially noteworthy are verses 25–28 where Jesus makes his complaint against them crystal clear, that their practices and lifestyle lead only to making clean “the outside of the cup and the plate”, while all the “greed and self-indulgence”, “all kinds of filth”, and “hypocrisy and lawlessness” remain on the inside. Jesus makes it clear that he stands for inner transformation of this darkness: “You blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup, so that the outside also may become clean” (v26). (See also 15.14 “they are blind guides of the blind”.)

On a similar theme, although less vitriolic, is Jesus’s encounter in John chapter 3 with the Pharisee Nicodemus, who is completely ignorant about the concept of spiritual rebirth. Jesus asks him: “Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand these things?” Jesus is again suggesting that he belongs to a tradition working on inner transformation, superior to the tradition of the Pharisees, who are portrayed in the gospels as being obsessed with the rules and regulations of outward behaviour, rather than seeking inner transformation. As Jesus says: “you lock people out of the kingdom of heaven. For you do not go in yourselves, and when others are going in, you stop them” (Matthew 23.13–14). (The same might be said about much of modern Christianity.) This is possibly why Paul, following his conversion, was so keen on freedom from the Law (Galatians chapter 3, Romans chapter 7).

Two other passages in John give revealing clues about Jesus’s tradition. Right at the start of his ministry Jesus is introduced to someone called Nathanael. “When Jesus first caught sight of Nathanael, he said: ‘Here is a real Israelite; there is nothing false in him’ ” (1.47). Extremely interesting is another passage (8.39–48) where, following a very feisty confrontation with some Jews, whom Jesus accuses of following the wrong religion and not recognising him as a true prophet, they assume that he must be a Samaritan. Is this a clue to understanding Jesus’s tradition?

Who exactly are the Samaritans? According to this source: “Samaritans consider themselves to be the true followers of the ancient Israelite religious line”. Also a Samaritan is a “member of a community, now nearly extinct, that claims to be related by blood to those Israelites of ancient Samaria who were not deported by the Assyrian conquerors of the kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE. The Samaritans call themselves Bene Yisrael (“Children of Israel”)…” (source).

It would seem therefore that there are two versions of ‘Judaism’, one pre-exilic and one post-exilic, and the pre-exilic tradition (the Samaritans) considered itself to be the authentic one, and the post-exilic version deviant and in some way inferior (possibly because of something that happened during the exile?).

Evidence for this point of view comes from the Qu’ran where a clear distinction is made between the Israelites (Banu Isra’il) and the Jews (al-Yahud). The Israelites are depicted as the historical ‘chosen’ people who were the ‘preferred’ of God in their time because they remained faithful to the original tradition (they are sometimes called the Nazarenes). The Jews, on the other hand, are spoken of as a religious community which pays special deference to Ezra: “The Jews say, ‘Ezra is the Son of God’… May they be damned by God: How perverse are they!” (9:30–31). (The same verse is equally uncomplimentary about Christianity.)

Let’s assume therefore that there must have been profound differences between the two traditions, that the post-exilic version of Judaism was essentially the creation of Ezra, and that the Samaritans were an Israelite sect which rejected the authority of Ezra. As an aside, it is interesting to note that the scholar Richard Friedman, having done extensive research, in his book Who Wrote the Bible? came to the conclusion that Ezra was the compiler/ final editor of the Old Testament. The scholar Kamal Salibi agrees: “The Hebrew Bible as we know it is essentially the product of the kingdom of Judah, rather than that of the rival kingdom of Israel… It was from Judah, not Israel, that the Jews as a religious community got the name by which they are still known”.

Putting all this information together, it seems clear that Judaism, with Ezra as its figurehead, was merely one tradition within Jewish culture, and there was a religious schism which pitted the orthodoxy of Judah, which survives as Judaism, against the heterodoxy of Israel. We therefore see that, far from being united, as Jews may wish to claim, there was a significant religious divide in the ‘Jewish’ culture of the time; there was an opposition movement, even if we don’t know how prominent and powerful it was. (A strong candidate for the first century version of this opposition would be the Essenes.)

It is now much clearer why the Pharisee Paul might want to oppose the followers of Jesus if, as the two passages in John’s gospel mentioned above suggest, Jesus considered himself to be a true Israelite, or a Samaritan as he appeared to the group of Jews.

Let’s now focus on Paul. He says that, immediately following his conversion, he went to Arabia without conferring with any human being (Galatians 1.17). (This raises serious doubts about the road-to-Damascus version of events in Acts chapter 9, especially verse 10 onwards. That’s a can of worms I won’t go into here.) This is extremely significant, because he goes to Arabia even though he was aware that the apostles who knew Jesus personally were based in Jerusalem. He does not say why he should go there, but from the context it must surely have been to learn about the new religion to which he had been converted. How he knew he should go there is not explained.

The information he needed about Jesus and his movement was therefore to be found in Arabia rather than Jerusalem. This means that there must have been some kind of outpost of the Israelite/Samaritan/Nazarene tradition there. It is quite possible, even likely, that he was shown there written texts (scriptures) from the tradition to which Jesus belonged that have now been lost. These might be the scriptures that he referred to in the quotes mentioned at the start of this article. Is there any evidence to support that suggestion?

Paul in one epistle (2 Timothy 4:13), expecting his imminent imprisonment and execution, asks Timothy to bring to him “the books, and above all the parchments”. That might be a reference to such scriptures. (I do know that Paul’s authorship of this epistle is contested. Whoever the author is, he may have this knowledge, so that this mention of books and obviously important parchments remains significant.)

One hypothesis is that in Arabia Paul must have discovered that an earlier prophet by the name of Issa had lived there a long time previously. That name looks nothing like Jesus to us, but apparently both names can be rendered as Iesous for ‘Jesus’ in Greek transliteration. (Modern Qu’ran translations actually call this figure Jesus.) It is believed that there was a gospel of this Issa written in Aramaic but now lost. Since some of its content seems to have found its way into the canonical gospels, it is a reasonable assumption that this is a text that Paul was introduced to in Arabia. Some of its contents appear also in the Qu’ran, where this Issa has some remarkable similarities to the story of Jesus:

- He was the son of a virgin Mary, and by implication her only child (19:16–34 and 3:42–53)

- He was born pure (19.19), and (like Adam) was not the product of human procreation (3.59)

- He was a man of God to whom a special ‘book’ was divinely delivered (19.30)

- He was endowed with the Holy Spirit, depending upon which translation you read (2.87 and 5.110)

- He was (or was called) the Christ (or Messiah Arabic al-Masih) (3.45, also 4.157, 171, 172, and 5.17, 72, 75, and 9.31)

- He worked miracles, and could bring the dead back to life (3.49ff)

- God made Issa ascend to him (4.158, also 3.55)

- He was to be brought to life again (19.33), to bear witness against unbelievers on the day of the Resurrection (4.159).

Luke is believed to have been a close associate of Paul. It is therefore likely that he would have had access to any literature in Paul’s possession, including this lost gospel. (It is likely that John also had access to a copy, but that isn’t a topic I’ll go into here.) Luke certainly had access to some sources unknown to the other gospel writers, for example the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. The most obvious example, however, is his lengthy prologue about the births and their foretelling of John the Baptist and Jesus. Where did he get this from?

Let’s note that his story concerning the virgin pregnancy of Mary and the birth of Jesus is identical with the one which the Qu’ran relates concerning Issa in a number of essential respects. The same is true of the story in the Qu’ran of the miraculous birth of the prophet Yahya to the aged priest Zechariah and his old and barren wife.

John the Baptist is a significant figure in all four gospels. However, only Luke says that John is the son of a priest called Zechariah (not to be confused with the prophet whose book appears in the Old Testament). The Qu’ran, also assumed to be depending on the now lost Gospel of Issa as a source, speaks of Zechariah as the father of the prophet Yahya, who was an older contemporary of the prophet Issa. Luke presents the same Zechariah as the father of John the Baptist — an older contemporary of Jesus (“In the days of King Herod of Judea”, 1.5). Why he should do this is something of a mystery, since Zechariah lived several centuries earlier, although one possibility is that he was trying to cover up what he was doing, disguising his source, the existence of which was supposed to be a secret. However, his mention of Zechariah suggests that he was taking his information directly from the now lost Gospel of Issa.

Circumstantial but persuasive evidence in support of this argument is that Luke begins his gospel in fluent Greek. Then quite suddenly the fluency ends and a more fumbling style begins as Luke starts to relate his Christmas story, which continues to the end of the Christmas narrative when the fluency of the introduction is resumed. Judging solely by the change of style, some scholars have suggested that the Christmas story in Luke must be a translation from a written source which was probably in Aramaic. From both angles of content and style, it therefore seems likely that Luke was indeed using the Aramaic Gospel of Issa as a source, a copy of which he presumably obtained from Paul. For some reason, as just noted and unlike Paul and John, he chose to use the material relating to the birth of Issa to portray the birth of Jesus, and the material related to the earlier prophet Yahya to portray the birth of John the Baptist.

There is therefore no reason to believe that Jesus’s mother was called Mary, since that was the name of Issa’s mother. That is a suggestion that will shock Christians, so let’s investigate that in more detail. Matthew, Mark and Luke do call her Mary. Paul, however, seems not to know the name of Jesus’s mother — in Galatians 4.4 he says that Jesus was “born of a woman” — which seems strange. Surely he must have known.

Most significantly, John seems to make a point of leaving her unnamed. This is especially noticeable at 6.42 where Joseph is named as the father but the mother remains unnamed. Also interesting is the wedding at Cana in chapter 2, where four times John merely says the “mother of Jesus” .

Most relevant to the argument, in chapter 19 (verses 25 and 26), he speaks of her as attending her son’s crucifixion accompanied by a sister called Mary, identified as Mary the wife of Clopas. I understand that, according to the customs of the time, the mother of Jesus could not have been called Mary if she really did have a sister by the same name. Some Christian commentators are aware of this, because they have tried to avoid the problem by claiming, without any supporting evidence, that they could not really have been sisters. (In the same way the Catholic Church tries to pretend that Jesus did not have any actual brothers and sisters, even though this is clearly stated in the gospels, because they have decided for reasons of their own, with no evidence whatsoever, that Mary was a perpetual virgin).

The mother of Issa, however, according to the Qu’ran is called Mary; this is repeated in various places. Therefore, if as John’s gospel suggests, Mary was not the name of Jesus’s mother, this would be strong evidence that the lost gospel of Issa was indeed the source for Mark, Matthew, and Luke. It is highly likely for Luke, since he almost certainly had access to a copy, and the other two may merely have been repeating a tradition without actual knowledge, thus second hand. It has, however, been argued that Matthew also had the Gospel of Issa, but in a Greek translation — in some places the same material is described with different words. Matthew perhaps did not know Aramaic, but Luke and John did.

SUMMARY and CONCLUSIONS

None of the above refers to the two quotations at the start of the article, but they were a convenient starting point, to establish the possibility that there are otherwise unknown sources for material in the New Testament. The significant hypotheses are that:

- if there was indeed a historical Jesus who lived in the first century (which some scholars doubt), he would have been a teacher/prophet in the Israelite/Samaritan/Nazarene tradition, following in the footsteps of the earlier Issa, and rejecting the Judaism of Ezra. Some of the material in the New Testament about him is identical to what was said of Issa.

- Paul, in Arabia, became aware of the scriptures relating to this prophet Issa.

- Luke had access to the original Aramaic Gospel of Issa, some contents of which survive in the Qu’ran. This seems indisputable because of his account of the circumstances surrounding the birth of John the Baptist.

Returning to the theme from earlier in the article, it is now much clearer why Paul might want to oppose the followers of Jesus. He says that he had been brought up as a Jew, and was now persecuting members of the rival Nazarene sect, who were followers of Issa. The Nazarenes apparently referred to their special faith or cult as ‘the Way’. In Acts, Paul uses exactly this term: “I persecuted this Way up to the point of death” (22:4).

Therefore Christianity may not be so much a New Covenant, as it claims, rather a return to the original Covenant. On the same lines, there is also the controversial possibility that Paul, far from introducing pagan and deviant elements into his new religion, was actually returning to the original true teachings.

===========================================================

The next two paragraphs are pure speculation on my part, not backed up by any knowledge or scholarly sources.

I’ve read from time to time that scholars and etymologists have no idea what the origin of the word Essene is. Is it just possible that it means followers of Issa? There is some similarity between the two words.

In the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Essene texts discovered at Qumran, most prominently in the Damascus document, there are mysterious references to an unnamed Teacher of Righteousness from the past, which have led to much speculation among scholars. Could that possibly be Issa? The description of him in the first two paragraphs of this wikipedia article certainly fits the bill in the light of what I was saying above about the Israelites and the Jews.

I said at the beginning that here I am revisiting a theme I’ve addressed earlier. Also, during this article I haven’t always provided sources. This is because I wanted what I’ve written here to stand on its own merits. It’s a long article but if anyone would like to go into this subject in more detail, please click here.

I hope you have enjoyed this article. I have written in the past about other topics, including spirituality, metaphysics, psychology, science, Christianity, and politics. All of those articles are on Medium, but the simplest way to see a guide to them is to visit my website (click here and here). My most recent articles, however, are only on Medium; for those please check out my lists.